It has been more than four years since the election of President Rodrigo Duterte, yet a few vocal members of the anti-Duterte social media commentariat are still blaming the Philippine Left for “supporting” the former Davao City mayor during and immediately after the 2016 national elections and therefore “enabling” his rise to power and dictatorship.

Recently, they seized on the torture and extrajudicial killing of long-time activist and National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) peace consultant Randall “Randy” Echanis as an opportunity to reiterate their accusations. They insinuate that Echanis, as a leader of leftist organizations, is partly to blame for his own death, which could only be the work of Duterte’s henchmen.

Raymond Palatino, Teddy Casiño and other activists have explained the Left’s attitude towards Duterte before, during and after 2016,1 effectively disputing the exaggerated claims of unconditional support and alliance-building. A bigger, more important question, however, needs to be asked: what enabled Duterte’s rise to the presidency?

Duterte and allies campaigning in Pandacan, Manila, in 2016. Wikipedia Commons

Not the Left

First things first: while the Left is a formidable presence and force in Philippine politics, it is still a secondary determinant of government policies, political shifts and electoral results in the country. While it considers the parliamentary struggle as important, it ranks this as a secondary form of struggle – and the electoral struggle as even more secondary. It could not be the main enabler of Duterte’s election and rule.

The number of votes garnered by candidates in the 2016 national elections are as follows: Duterte, 16.6 million; senator Mar Roxas, 9.98 million; senator Grace Poe, 9.1 million; vice-president Jejomar Binay, 5.42 million; and senator Miriam Defensor-Santiago, 1.46 million.2 Such a huge lead cannot be explained by the Left’s support.

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, served asPresident of the Philippines from 2001to 2010. Wikipedia Commons

If we are to search for the entities behind Duterte’s ascent to, and hold on, the presidency, we should look at the political forces that wield economic and political power in the country: foreign powers, the ruling elite of comprador capitalists and landlords – and the regimes that represented them for a period of time.

Also to blame are the neoliberal and fascist policies implemented by successive post-Edsa 1986 regimes, and were intensified by the regimes of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (2001-2010) and Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III (2010-2016). These policies laid the conditions that were exploited by Duterte in his electoral campaign.

The philosopher Slavoj Zizek popularized a quote that he attributes to Marxist thinker Walter Benjamin: “Every rise of Fascism bears witness to a failed revolution.”3 This runs counter to the Philippines’ first experience with open fascist rule. When president Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972, the revolutionary movement was gaining strength, but not on the brink of seizing state power, and cannot be called a failure. It even grew under the Marcos fascist dictatorship.

Duterte’s rise is also different from the European experience with fascism in the middle of the 20th century, of which Benjamin was a witness and victim. While Duterte’s dictatorship is part of the neocolonial elites’ project of destroying the Left, the revolutionary movement in the Philippines is still emergent and cannot be considered a failure. Furthermore, Duterte’s election was largely shaped by a struggle among foreign powers and local elites for political power.

Foreign powers, local elite

We know by now the political forces that supported Duterte’s candidacy for president: Arroyo and the Marcos family. Arroyo was imprisoned by Aquino, and was repeatedly blamed by the latter for the problems facing the country. The Marcoses are historical foes of the Aquinos, were further marginalized during Aquino’s term, and can even be described as a spent force during that time. Arroyo and the Marcoses wanted badly to return to power to, at the very least, save themselves from being held accountable for their crimes and from being demonized. Also among Duterte’s backers were the wealthy political dynasty of Manuel “Manny” Villar and other politicians.

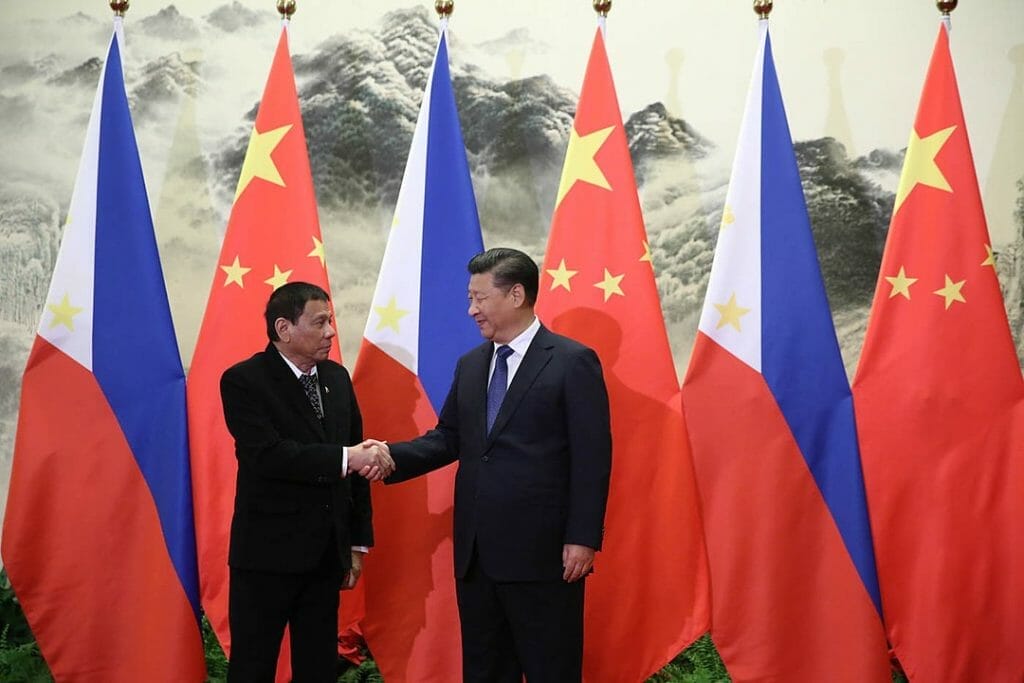

President Rodrigo Roa Duterte and People’s Republic of China President Xi Jinping shake hands prior to their bilateral meetings at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on October 20. Wikipedia Commons

It is reasonable to think that China also supported Duterte. The Asian superpower had reasons to do so: his statements and promises regarding China-Philippines relations during the election campaign; China’s adversarial relations with the Aquino regime and its candidate which stemmed from the regime’s rabid pro-US stand on China and opposition to China’s aggressive territorial claims in the South China Sea; and the backing of Arroyo, who forged close relations with China during her presidency.4 One could only imagine the amount of resources that China poured into Duterte’s campaign.

The US, meanwhile, appeared confident and complacent that elections in its longstanding necolonial outpost will not yield a president with divided loyalties to it and China. It was most likely swayed by the confidence of the solidly pro-US Aquino faction of the ruling elites, and Duterte’s lead in the race became apparent only a few months before election day. Duterte furthermore tried to hide his true pro-China colors until the last minute and feigned obeisance to the US. It was also the twilight period of the US’ Barack Obama administration, already facing the challenge posed by Donald Trump’s campaign.

Manuel “Mar” Araneta Roxas II, the standard-bearer of the Liberal Party for the 2016 presidential election. He was officially endorsed by President Aquino to continue the present administration’s reforms. Wikipedia Commons

Even as political elites associated with martial rule (Marcoses) and Marcosian rule (Arroyo), together with China, were solidly behind Duterte, the Aquino faction was so overconfident with its popularity and so hellbent on getting Roxas elected that it failed to read the situation and forge unity with the Poe and Binay factions. It was too late in the election campaign when Roxas called for unity – and it seems only with the objective of scoring points against the two candidates.

Worse, while Duterte was making bold promises to the electorate and acting like a plainspoken man of the people who is greeted by the public like a rockstar, the three candidates ran a ho-hum campaign, basically promising the continuation of Aquino rule. They grossly misjudged the changed public sentiment towards the Aquino regime, which by the end of its term had proven the inanity of its central slogan – “Kung walang corrupt, walang mahirap (without corruption, there will be no poverty).” They were forced to ape some of the exact promises made by Duterte.

Economic policies

To gather popular support for his candidacy, Duterte made audacious – and, in hindsight, deceptive – promises to the electorate: a “stop” to contractual employment among workers, to land-use conversion which adversely affects farmers, to large-scale mining that destroys the environment and drives away indigenous peoples from their land, among others. He also promised free college education, which is most appealing to students and the youth. By promising to resume peace talks with the NDFP, he signaled openness to more radical economic reforms.

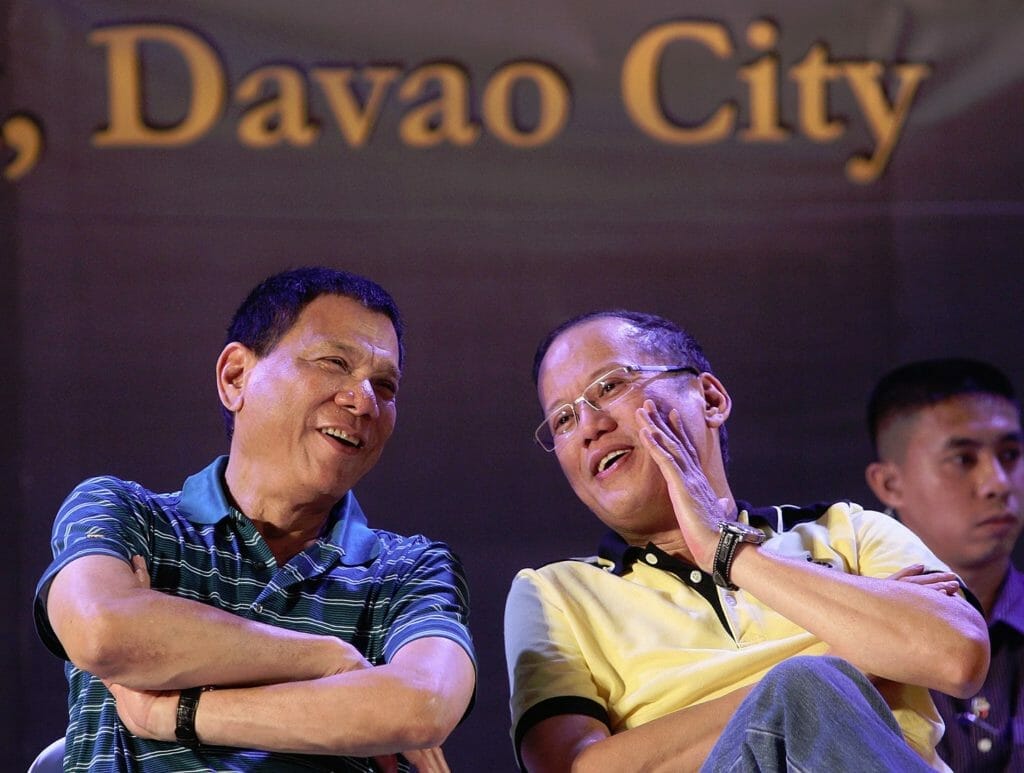

Then-Mayor Duterte (left) with then-President Benigno Aquino III during a meeting with local government unit leaders in Davao City in 2013. Wikipedia Commons

Duterte, in effect, became the first post-Edsa big league presidentiable to promise policies anathema to neoliberalism and the neoliberal consensus of post-Edsa regimes. These policies began to be laid down during the Marcos dictatorship and were escalated under the presidencies of Cory Aquino (1986-1992) and Fidel Ramos (1992-1998). After the short presidency of Joseph Estrada (1998-2001), these policies went full blast under the nine years of the Arroyo regime.

These policies were upheld by both Arroyo, whose stint was marred by corruption cases, and by Aquino, known for his anti-corruption “straight path” rhetoric. Despite their political rivalry, most of Arroyo’s polices were upheld by Aquino. By the end of his six years in office, Aquino had become a “poster boy” of neoliberal economic policies, says independent think-tank Ibon Foundation. His presidency was feted for meeting all the markers of neoliberal success, including a rise in Foreign Direct Investment and commendations from foreign powers for the country’s supposed economic stability.

Yet data on poverty, employment, and other socioeconomic conditions painted a different picture; the people suffered “worsening conditions.” Aquino’s economic legacy includes “an unprecedented jobs crisis, [the use of] public funds to guarantee private profits, an even wider gap between rich and poor, and economic subservience to foreign dictates.”5

So when Duterte promised to take the country in a different direction, he won over a section of the critical-minded electorate, many among the poor, and a segment of the Left – even as the Makabayang Koalisyon ng Mamamayan or Makabayan, the progressive electoral formation, stuck to supporting Poe.6 On top of these promises, and to further woo the Left as a political force, Duterte vowed to release political prisoners and resume peace talks with the NDFP. The offer of cabinet positions came after the election.

Military and police

Another political force that Duterte courted were the military and the police. Duterte ran on a strong peace and order platform and a strongman image, swearing to wipe out drugs and criminality in the first three months of his term. Even as he was promising policies that would give economic relief to ordinary Filipinos, he was warning about a bloodbath, a “war on drugs” – a nationalization of the extrajudicial killings of suspected drug addicts and pushers and other criminals that he undertook when he was Davao City mayor.

Such a stance could only have appealed to the military and the police. Both institutions are tarnished by a long history of human-rights violations, encouraged by regimes that use them as a weapon against political opponents, especially the Left.

President Rodrigo Duterte presents a chart illustrating a drug trade network of high level drug syndicates in the Philippines during a press conference, July 7, 2016. Wikipedia Commons

This is especially true during the nine years of the Arroyo regime: 1,188 extra-judicial killings, 205 enforced disappearances, among other human-rights violations from January 2001 to December 2009, according to rights group Karapatan.7 Arroyo was also accused of militarizing her government, that is, appointing retired military and police generals to many civilian posts.

Despite riding the wave of anti-Arroyo sentiment, generated and sustained by the Left, in his bid for the presidency, Aquino refused to even hold a dialogue with the Left during the 2010 elections. Fascist repression continued under his six-year term: 307 victims of extra-judicial killings, 30 cases of enforced disappearances, and other human-rights violations, according to Karapatan.8

Thus the military and the police continued to become a strong political force in the country under Aquino. Duterte was also able to take advantage of the Mamasapano bloodbath of January 2015, a botched counter-terrorist operation led by Aquino that left 44 members of the military’s elite Special Action Force dead. Hurting from the biggest political scandal that hit the Aquino regime, the military and the police found Duterte’s promises most appealing.

It can be said that Duterte not only vowed to give the police and military higher salaries and benefits, he promised them no less than military and police rule over the country. He guaranteed them protection and complete impunity in attacking the enemies that he identifies. Now, it can be said: this is the promise on which he actually delivered.

President Rodrigo Roa Duterte caricature. Image: thongyhod / Shutterstock.com

Blame game

Given all these, blaming the Left for Duterte’s rise to power is wrong on so many levels:

- It is intellectually untenable and dishonest, as it obscures the vastly more significant factors that caused and contributed to his rise to power. The unprecedented shock and outrage roused by Duterte’s extremely murderous and cronyist regime should not hide the accountability of the age-old powers that rule the country and their long-standing policies.

- It adds insult to the injury being suffered by the Left under Duterte. Faced with the openings provided by Duterte to it, the Left had no choice but to “take the opportunity of working with the government to initiate and support progressive policies and programs while exposing and opposing those which were reactionary and anti-people,” as Casiño said in a recent post in his Facebook Page. It was, as such, critical of Duterte’s bloody “drug war” from the start, even as it pushed for the reforms that Duterte promised.

Since Duterte became president and especially after it became completely oppositional to the regime around the third quarter of 2017,9 the Left has been the most consistent and vocal in fighting his anti-people policies, more in fact than any sector of society. Duterte has been increasingly vociferous in attacking the Left, but the latter shows no signs of backing down.

- It distracts the growing number of people who are becoming critical of Duterte’s regime from the real culprits for the crime of putting him in power: primarily China, the US, Arroyo, the Marcoses, other factions of the country’s political elite and secondarily the Aquino faction of the ruling elite. Those with blood in their hands are getting away, and those that are bloodied by the regime’s attacks are being blamed. It also conceals the neoliberal and fascist policies that brought about the conditions that Duterte took advantage of during his presidential campaign.

- Finally, especially with the implication that the Left deserves the attacks that it is facing under Duterte, it divides and weakens the broad opposition to the Duterte regime. It objectively redounds to the benefit of Duterte and his true enablers. It ignores the lessons provided by the successful resistance and ouster movements against the Marcos dictatorship and the Estrada regime. The Left was not just another political force in those movements; it was their muscle and backbone. It plays a major role in the efforts of arousing, organizing and mobilizing people, which has proven to be decisive in fighting and ousting oppressive regimes.

Faced with mounting outrage over its criminal responsibility for allowing the spread of Covid-19, for its militaristic approach to the health crisis, and for non-stop offensives on critical and independent voices, the Duterte regime is most likely to intensify its attacks against the Left and the broad opposition in the coming months and years.

It is time to stop scapegoating the Left for Duterte’s rise, to blame and fight the real culprits – foreign powers, political elites, previous regimes and their policies – and to forge stronger unities and intensify the struggle against the cronyist and dictatorial regime.

Teo S. Marasigan

- Raymond Palatino, “Did the Left Enable Duterte’s Deadly Regime?,” Manila Today, February 2018. https://manilatoday.net/left-enable-dutertes-deadly-regime/

Teddy A. Casiño, “Duterte’s falling out with the Left,” Rappler.com, September 9, 2017.

https://rappler.com/voices/thought-leaders/duterte-falling-out-left - “2016 Presidential Election Results,” Rappler.com, May 2016. https://ph.rappler.com/elections/2016/results/philippines/position/1/president

- lavoj Zizek, “How to Read Lacan,” Lacan dot com, 2013. https://www.lacan.com/essays/?page_id=261

- Renato Cruz de Castro, “From antagonistic to close neighbors? Twenty-first century Philippines-China relations,” in Mark R. Thompson and Eric Vincent C. Batalla, editors, Routledge Handbook of the Contemporary Philippines. London and New York: Routldedge, 2018.

- Ibon Media and Communications, “Elitist politics and economics: the real Aquino legacy,” Ibon Foundation, July 1, 2016. https://www.ibon.org/elitist-politics-and-economics-the-real-aquino-legacy/

- Teddy A. Casiño, “Why I will vote for Grace Poe,” https://teddycasino.wordpress.com/2016/05/04/why-i-will-vote-for-grace-poe/

- Karapatan, “Reign of Terror, Climate of Impunity” in Ibon Foundation, Inc., Oplan Bantay-Laya: the US-Arroyo Campaign of Terror and Counterinsurgency in the Philippines. Quezon City: Ibon Books, 2010.

- “2015 Karapatan Year-end Report on the Human Rights Situation in the Philippines,” Karapatan, July 13, 2016. https://www.karapatan.org/2015+Human+Rights+Report

- Teddy A. Casiño, “Did the Left ‘enable’ Duterte?” Facebook Post, August 19, 2020. https://web.facebook.com/followteddycasino/posts/10158629401459028